By Dr Mylène Dubiau (Project Co-Director, Université Toulouse II – Jean Jaurès)

Project Co-Director Dr Mylène Dubiau explores a rare Baudelaire setting by a composer close to her own research base in Toulouse

Looking at manuscripts might seem a boring thing to do, but as we try to locate a source, it is like a treasure hunt, and some discoveries can bring out new understandings of published works we thought we knew. Baudelaire was very influential on French composers of the Mélodie française genre (one voice singing a poem with piano accompaniment) by the end of the nineteenth-century in France. Well-known musical versions by Debussy or Duparc are a case in point, but Baudelaire’s poetry spreads out beyond Parisian circles not only poetically but also musically.

Ten years younger than Debussy, Déodat de Séverac (1872-1921) was a French composer known primarily for his piano pieces, such as En Languedoc and Cerdana, inspired by the atmosphere of the South of France, his native region. Yet he wrote several important mélodies: collections or isolated pieces on verses of major French poets. As he was taught in the recognized Abbaye de Sorèze[1], he had a very refined literary education, wrote criticism and poetry of his own, published as Écrits, and was friends with important contemporary writers, among them Guillaume Apollinaire and Jean Moréas. Baudelaire was one of his regular readings, alongside Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarmé.

The corpus of the melodies of Séverac is important: formed of isolated pages and several collections, including the Flors d’Occitania (1910), he is influenced by regionalism and folklorism with lot of poetry. He nevertheless went to Paris and followed the traditional education of the prestigious Schola Cantorum[2], and declared himself to be a ‘musician-farmer’.

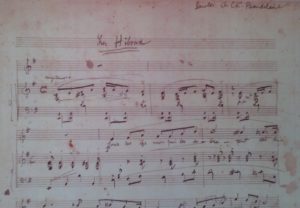

Séverac set only one poem of Baudelaire to music, Les Hiboux (The Owls), first in 1898, drafting it three times, before revising the setting in 1911 and publishing it finally in 1913. His initial intent had been to publish his first manuscript in February-March 1898, with a cover sketched by his friend Lamasson.[3] However, the publication of this version never happened, and in fact the composer may not have been satisfied with his first musical esquisse as he made substantial changes a decade later. But looking at his first drafts can be very useful for us as we explore his understanding of Baudelaire’s poetry.

In Les Hiboux, the double meaning of the representation of the owls – inspired by oriental pictures perceiving them as symbols of wisdom, or ironic depictions of contemporary politicians[4] – may have been difficult to set to music. How can the composer insert irony in his musical setting? And to what extent can the musical effect of the illustration of the owls be found in Séverac’s mélodie?

These were the questions I had in mind knowing the final version of Déodat de Séverac’s setting of Les Hiboux, with his static harmonic figure and formulas of sharp “chirping” of birds in the upper piano line.

But as Déodat de Séverac is one of the famous local composers around Toulouse where I am based, and because the Association Déodat de Séverac is very active in Saint-Felix-de-Lauragais, just one hour east of Toulouse, I decided to check for other sources. With the help of the opera singer and artistic director the Association Déodat de Séverac, Jean-Jacques Cubaynes, who I knew through our project partner Association Toulouse-Mélodie-Française, I was able to gain rare access to the earlier manuscript versions of the Séverac setting, and discovered three comprehensive drafts of Les Hiboux, written at the very end of the nineteenth century.

Manuscript versions

While the first thought that comes to mind when listening to the published setting of Les Hiboux could be that Séverac portrayed only the scene of owls perched in their natural habitat, in fact I found that his rewriting of the work in 1911 places emphasis on the perception of time throughout his setting, according to the symbolic meaning of Baudelaire’s text.

What grabs my attention in the discrepancies between the first version in 1898 and the 1911 one is not so much the vocal part (although this does differ in melodic shape in quite a few instances), but especially the piano part, which, for me, sheds light on a new process of composition.

The beginning of the third draft score in 1898, a refinement of the two previous ones, presents a melodic motive that will be repeated and developed, transposed and given to the voice during the song, as a “typical” technique used in the music composition process. But the 1911 version abandons this motive, focusing only on the static harmonic presentation, with open fifths, and little repeated rhythmic movement. The “majestuoso” of the first version becomes a “lento” marking, stressing the sententious tone of the revised mélodie.

The idea of movement (or a lack of it, or immobility) is played out across the score, and the significant changes between the two versions are expressed with more and more subtlety, always coming back to the idea of inexorable rhythm (or non-rhythm!). At the end of the 1911 version, what is stressed is the “ivresse” (“intoxication”) of the human being, who is trying to move forward, but always comes up against the vacuity of their movements, reinforced by the highly stylized hieratic accompaniment.

Finally, the rewriting of the song appears to make this absence of mobility more acute, and this idea finds its correspondance with the rhythmical work of the poet. The composer built a narrative that may shed light on the essential understanding of this fable with a closing moral – that life is vacuous and empty.

And this is a very important idea in Baudelaire’s work. The tension between something static and something moving, the paradox between the known and the new is exactly Baudelaire’s concept of the modernity in art, as he writes in Salon de 1859:

« la modernité, c’est le transitoire, le fugitif, le contingent, la moitié de l’art, dont l’autre moitié est l’éternel et l’immuable ».

“Modernity, is the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent, that half of art of which the other is the eternal and the unchanging.”

The tension between immobility and movement in the poem foregrounds the significance of playing with the perception of time in music for Déodat de Séverac, beyond just the simple evocation of the wise bird with blinking eyes towards the symbolism present in the poem. The modulation of temporality is a modern goal that aligns with other composers’ studies in the early years of the 20th Century – among them Debussy and his “mystery of the moment”, to quote Jankélévitch. Baudelaire’s poem was no doubt a revealing poem that served to lead Déodat de Séverac to this point, and helped him to bring out modernity in song, decades after his own modernity in poetry.

[1] ‘This Benedictine abbey, established in 754 at the foot of the Black Mountains, owes its fame to the mode of innovative teaching which it practised from the 17th century up to its closure in 1991. Its fame is such that it was set up under Louis XVI as a Royal Military School and welcomed within its walls pupils from all over the world.’

[2] A follower of Vincent D’Indy in the Schola Cantorum, he also followed the education of Bordes, Guilmant and Magnard.

[3] Cf. Déodat de Séverac, La musique et les lettres, correspondance rassemblée par Pierre Guillot, p. 45 : [à Jeanne de Séverac, Paris, février-mars 1898] : « Comme j’ai l’intention de faire éditer Les Hiboux, ces renseignements [sur les procédés nouveaux de la photo-lithographie] pourraient m’être fort utiles pour la couverture. L’ami Lamasson m’a déjà fait une esquisse charmante, encore à l’état de larve, mais bien original. » (“As I intend to get Les Hiboux published, this information [on the new techniques of photo-lithography] would be very useful for me for the cover. My friend Lamasson has already produced a charming sketch for me, still in first draft, but very original.”).

[4] Cf. Claude Pichois’ notes in the Pléïade edition of Baudelaire.