By Dr Caroline Ardrey (Project Research Associate)

Project Research Associate Dr Caroline Ardrey looks to computational analysis to examine why Baudelaire is still so popular with composers and singers.

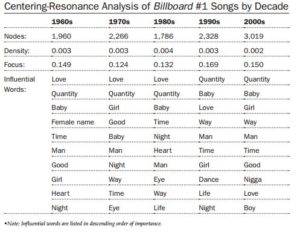

In 2014 David H. Henard and Christian L. Rossetti at North Carolina State University published the results of a study which charted the most commonly occurring themes in popular music from 1969 – 2009. Taking Billboard magazine’s monthly run-down of the top 100 songs during this period, the researchers, who are specialists in marketing and management, used computer analysis techniques to pick out the most influential words, based on factors such as the frequency of particular words and time spent in the charts, across a body of just under 1000 songs.

Source: David H. Henard & Christian L. Rossetti, “All You Need is Love? Communication Insights From Pop Music’s Number-One Hits”, Journal of Advertising Research, June 2014

This information was then used to plot the dominant themes in popular music of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. These are as follows:

- Loss

- Desire

- Aspiration

- Break-up

- Pain

- Inspiration

- Nostalgia

- Rebellion

- Jaded

- Desperation

- Escapism

- Confusion

The overall results are fairly unsurprising — there are few pop songs which don’t feature themes of loss, desire, pain, aspiration, inspiration or rebellion. When I read Henard and Rossetti’s paper , I did a little mental run-down of the pop songs I’d heard on the radio, on the television, on YouTube adverts and in shops (rather than songs I’d chosen to listen to) over the past few weeks, just to make sure. In my list, there was Bryan Adams’s “Summer of ’69” (nostalgia – check!), Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin'” (aspiration – check!), Jess Glynne’s “Hold My Hand” (desire – check!), Sinead O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” (break-up, pain, loss, the list goes on…). Obviously, this little test is very subjective and not nearly as rigorous or scientific as the North Carolina State University study but my own sample group seemed to support these findings — try it for yourself…!

Predicting the hits of the future

Although the study found that the dominant topics in popular music fluctuate a little from one decade to another , Henard and Rossetti argue that the twelve communication themes listed above “are used repeatedly over time; are largely emotional in nature; appear congruent with contemporary societal and environmental influences; and help predict a song’s chances of commercial success.” [1] The research shows that looking back at themes from the music of the recent past can help socio-musicologists predict a future hit — this is clearly helpful information for major commercial songwriters. This research also has another application in helping us to understand why certain songs have been so popular and have stood the test of time.

There is, of course, more to making a multi-platinum hit than some poignant, emotive lyrics — a catchy, beautiful or motivational tune also goes a long way. We should be careful not to fall into the trap of separating out words and music — the two elements are melded together in song and their inextricably is a fundamental part of what song is; nevertheless, the research team at North Carolina State University have tapped into an important part of what makes a big hit. Based on the findings of Henard and Rossetti’s study, it would seem that songs which make the big time are those which have an emotional content and are relevant to the major and minor experiences of their audience – that is the general public.

Common themes in poetry and song

Poetry, too, often has an emotional content, speaking of experiences which are familiar to its readers. Stylist Magazine recently published a feature on the “50 most poignant themes in poetry” — amongst the poems selected were Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy”, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “How Do I Love Thee?” and Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 18” (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day…?”). Without exception, the short excerpts from famous English-language poems highlighted by Stylist Magazine fall into the same twelve thematic categories as the top 100 Billboard hits from 1969-2009. It seems that, just as with pop music, people respond to and appreciate poetry which articulates (or tries to articulate) familiar and often emotionally challenging experiences.

With this in mind, I wondered whether the major themes in Baudelaire’s poetry might offer the key understanding why his work has been so popular with singers and songwriters spanning different historical moments, wide-ranging musical genres and diverse languages. In order to make some steps towards testing out this hypothesis, I took a similar (albeit more simplistic) approach to Henard and Rossetti, using an online tool called Voyant, created by Stéfan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell, to find out which words appeared most frequently, across all 129 poems in the 1861 edition of Les Fleurs du Mal. The results were striking. The ten most occurring words in the corpus were (number of instances in brackets):

- cœur [heart] (95)

- yeux [eyes] (75)

- ciel [sky] (56)

- âme [soul] (45)

- soleil [sun] (42)

- corps [body] (35)

- vieux [old] (35)

- beauté [beauty] (34)

- soir [evening] (33)

- mort [death] (32)

Not all of these appear in the lists of influential words in pop music from the 1960s to the 2000s, but given that there is a whole century between the publication of this edition of Les Fleurs du Mal and even the earliest songs in Henard and Rossetti’s study, there is a surprisingly strong correlation between the two sets of data.

Using the word frequency data generated by uploading the text of Les Fleurs du Mal into the Voyant digital text analysis tool, I was able to produce a list of the top twelve themes in Baudelaire’s verse poetry.

- love (heart)

- beauty (beauty, sight, attractiveness)

- desire (sexuality)

- women (beauty, the female body)

- death (mortality)

- jaded (spleen, darkness, night)

- aspiration (ideal, heaven, sky)

- the soul (spirit)

- the poet (poetry)

- time (aging, the past, the seasons)

- nostalgia (memory, regret)

- escapism (wine, heaven, distance)

Source: Voyant Analysis (C. Ardrey, May 2016)

NB: the order of importance of these themes will vary depending on factors such as grouping of words,grammatical position / function etc.

It’s worth mentioning here that, in order to highlight the similarity between the two thematic lists, I’ve stuck to the same terms as used in Henard and Rossetti’s paper, though I have added some qualifying words and sub-themes, to illustrate the word groupings I considered in order to arrive at these overarching themes. While the list is not exactly the same, there is an obvious resonance between the most prevalent themes in popular music, according to the North Carolina State University study, and the dominant themes of Les Fleurs du Mal. What’s more, there is not one of the Billboard hit themes identified by Henard and Rossetti which does not also appear as a theme in Baudelaire’s poetry. This is perhaps more easily visualised by the word cloud we produced early on in the Baudelaire Song Project, which offers a (non-exhaustive) overview of the themes present in Les Fleurs du Mal.

While rebellion doesn’t emerge as a common theme based on word-frequency data and isn’t easily identifiable in the word cloud, it is undeniably an important theme in Baudelaire’s oeuvre. After all, this is the poet who had six poems censored for discussing themes such as lesbianism and vampiricism, and who published a poem entitled “Le Rebelle” (“The Rebel”), which is said to have inspired PJ Harvey’s 2009 song “Pig Will Not”. [2] The desperation described by modern musicians is almost ubiquitous in Les Fleurs du Mal and is bound-up with music, which, in the final lines of “La Musique” the poet likens to a “great mirror / of my despair” [3]

Baudelaire in the twenty-first century

These are only preliminary investigations and there’s a degree of subjectivity in assigning themes based on word-frequency alone, as Henard and Rossetti warn in their article. [4] To gain a fuller understanding of the thematic relationship between Baudelaire’s poetry and song settings of his works, we would need to consider other factors, such as the number of song settings of individual poems, which, in turn, affects the weighting given towards particular themes across the whole corpus of songs in our sample group. There are certainly limitations in the method of establishing themes in poetry based on word-level analysis alone; after all, part of the beauty of poetry is in its “slipperiness”, in its use of metaphor and in the diversity of its vocabulary, in all of the elements which make it so difficult to analyse through computational methods. The particular polyvalence of poetic language means that in trying to pick out key themes in the work of Baudelaire, or of any other poet, through language-frequency analysis, we risk missing those which are expressed in unusual or metaphorical terms, and thus under- or overestimating the importance of particular themes. Nevertheless, the very simple comparison of word frequencies in Baudelaire’s poetry with central concepts of Billboard hits is sufficient to demonstrate that there is a close link between the themes in Les Fleurs du Mal and those which appear time and time again in pop music.

This comparison highlights just how relevant Baudelaire’s poetry is to a contemporary audience, tapping into emotive themes in a way which still resonates with so many readers, not only in the original French but also in translations. It is, at least in part, this continued relevance which makes his poetry popular with contemporary singers and composers. If, as Henard and Rossetti assert, drawing on familiar and emotive subjects such as desire, nostalgia and rebellion in popular music increases the chances of creating a hit, [5] then perhaps, in the future, more musicians will turn to the poetry of Baudelaire and his contemporaries for timeless, ready-made song lyrics which tap into the emotional sensibilities of the mp3-downloading public and have the potential to be a chart-topping sensation.

Notes

[1] Abstract, “All You Need is Love? Communication Insights From Pop Music’s Number-One Hits”, Journal of Advertising Research, June 2014, [178-191], 178.

[2] There are various sources which affirm the influence of Baudelaire in the writing of PJ Harvey’s “Pig Will Not”. cf.http://www.slantmagazine.com/music/review/pj-harvey-and-john-parish-a-woman-a-man-walked-by

[3] Translation my own.

[4] Henard and Rossetti were well aware of the problems of studying texts using word frequency. They apply more advanced methods of computational analysis in their own study: e.g. considering grammatical relationships between words; they also take measures such as discounting non-commercially successful songs to eliminate bias. cf. “All You Need is Love? Communication Insights From Pop Music’s Number-One Hits”, Journal of Advertising Research, June 2014, [178-191], 181.

[5]”All You Need is Love? Communication Insights From Pop Music’s Number-One Hits”, Journal of Advertising Research, June 2014, [178-191], 179-180.